Jennie Klein on Frans van Lent

Transcription of a performance: A chain by Frans van Lent

I drove my car to the castle of Hautefort and parked at the top of the hill.

I left the car, picked up a pebble (1) and walked down the hill. At the fork, I dropped the pebble and picked up a dandelion leaf (2).

I walked further down, dropped the leaf (3) and collected a fallen twig. I walked on to the corner near the Mairie, where I dropped the twig (4) and picked up a piece of stone.

From there I walked to the right (5), dropped the stone and found a dried laurel leaf. Holding this leaf I walked to the old garage.

I dropped the leaf (6) and picked up a crushed piece of reed. I walked up the street to the wall of the castle gardens, let go of the reed and picked up a rose sprig. No flower, just thorns.

I walked to the left, down the hill, past the castle, where I dropped the sprig in front of a fence. There I picked up a small piece of gravel, walked down the steps to the road. I walked along the road to the right, to where I could climb again, next to the Auberge. There I let go of the piece of gravel (9) and picked up a lump of cement.

I climbed all the way up to the castle where I dropped the cement (10) and, on the side of the street, picked up the chip from a wooden board. I followed the road, past the castle, to the fork next to the parking lot (11).

I let go of the wood and picked up the first pebble I had dropped at the beginning of the walk (2). I walked back to my car, dropped the pebble (1), got in and drove off.

‘PERFORMANCE ON THE BORDER OF VISIBILITY’

TEXT BY JENNIE KLEIN

Thirty years ago, Peggy Phelan published Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (Routledge), in which she argued that the power of performance as an art forms lies in its inevitable disappearance. Published in 1993 as video technology was just becoming available, Unmarked referenced a different, earlier economy of performance art, one in which description was more important than documentation, and it was often difficult to find either, since most were tucked away in limited run catalogs. Within 15 years, the iphone and the internet had changed everything. Performance art no longer disappeared. Instead, it continued to live on social media platforms, artist websites, and art publications.

The workshop Performance on the Border of Visibility, led by Frans van Lent for the 2022 Flow Festival, was about returning to the idea of the unmarked/unremarkable performance. Over two days, van Lent encouraged participants to think about making public performances that disappeared into the public space. Only the artist would know that they were performing. The public audience who encountered the piece would not be aware that anything was different, out of the ordinary, or amiss.

According to the description provided by van Lent for the Flow Festival:

The unnoticed performance takes place as a private event, embedded in public space.

In this line of thinking, performance is similar to any other personally motivated activity in public space.

This workshop is about the 'overflow area' in which the private manifests (and hides) in the public.

Day One Workshop Assignment by Frans van Lent

Why hide a performance from its public? There are many reasons, first and foremost because the necessity of copious documentation has meant that the audience who longs to experience the performance in community with the artist often finds their view blocked by the people in charge of documenting the performance, who are always entitled to the front row seat. For van Lent, the unnoticed private performance events that takes place in public have a profound effect for those who participate. Unnoticed performances, which rely on volunteers as well as artists, create community amongst those who participate. They are non-violent, peaceful forms of resistance to the status quo. The actions are so subtle, so minimalist, that they go unnoticed by the uninitiated. Nevertheless, these actions, which challenge the Western construction of productivity and efficiency, pose a viable alternative to the idea that artists must always promote themselves, suggesting instead that artists, volunteers, and audiences slow down, take time to observe, and live mindfully. As van Lent suggested in Unnoticed Art, a modest and unassuming book that was generously gifted to all of the workshop participants, unnoticed art embraces the fact that genuine engagement will be limited to a small group of those involved. I assume that, because of not being perceived by others, because of this public privacy, the performer will experience the connection with the work and with the group more intense (sic).

To explain the significance of unnoticed art, van Lent cites In a Train, a performance that he organized in 2013. 5 performers joined him in a performance on a train traveling 200 k/per hour between Amsterdam and Berlin. In a Train was set up as a performance for 6 people executing obvious movements. The performers for In a Train were very aware of one another and of the passengers, becoming a team by the end the performance. The audience–the passengers on the train–remained unaware and uninvolved with the performance. For van Lent, who would go on to organize two Unnoticed Art festivals, this was an epiphany. Prior to doing this performance, van Lent was doing solo performances for the camera. The audience observed the piece “at another time, in another space, and through another medium.” Seeking to alter this relationship, van Lent realized that In a Train had allowed him to “turn the performers into spectators, and the spectators into performers.” For the first iteration of the Unnoticed Art Festival in 2014, no visual documentation was made of the actions.

The workshop begin with introductions, followed by an explanation of unnoticed art, which included the story about In a Train. Van Lent then gave the participants a simple task: staying in your private space, move an object from one place to another, being conscious of the sculptural volume of the space and the object, and the relationship between the two. Participants were able to document their action in any form that they wished. Given the questions that arose after the assignment, it was clear that most people planned to take a video with their phone. The group was given two hours, after which they reconvened to share what they had done. There were a lot of interesting projects, including two that essentially used the phone as the object, creating short video pieces that were literally shot from the hip.

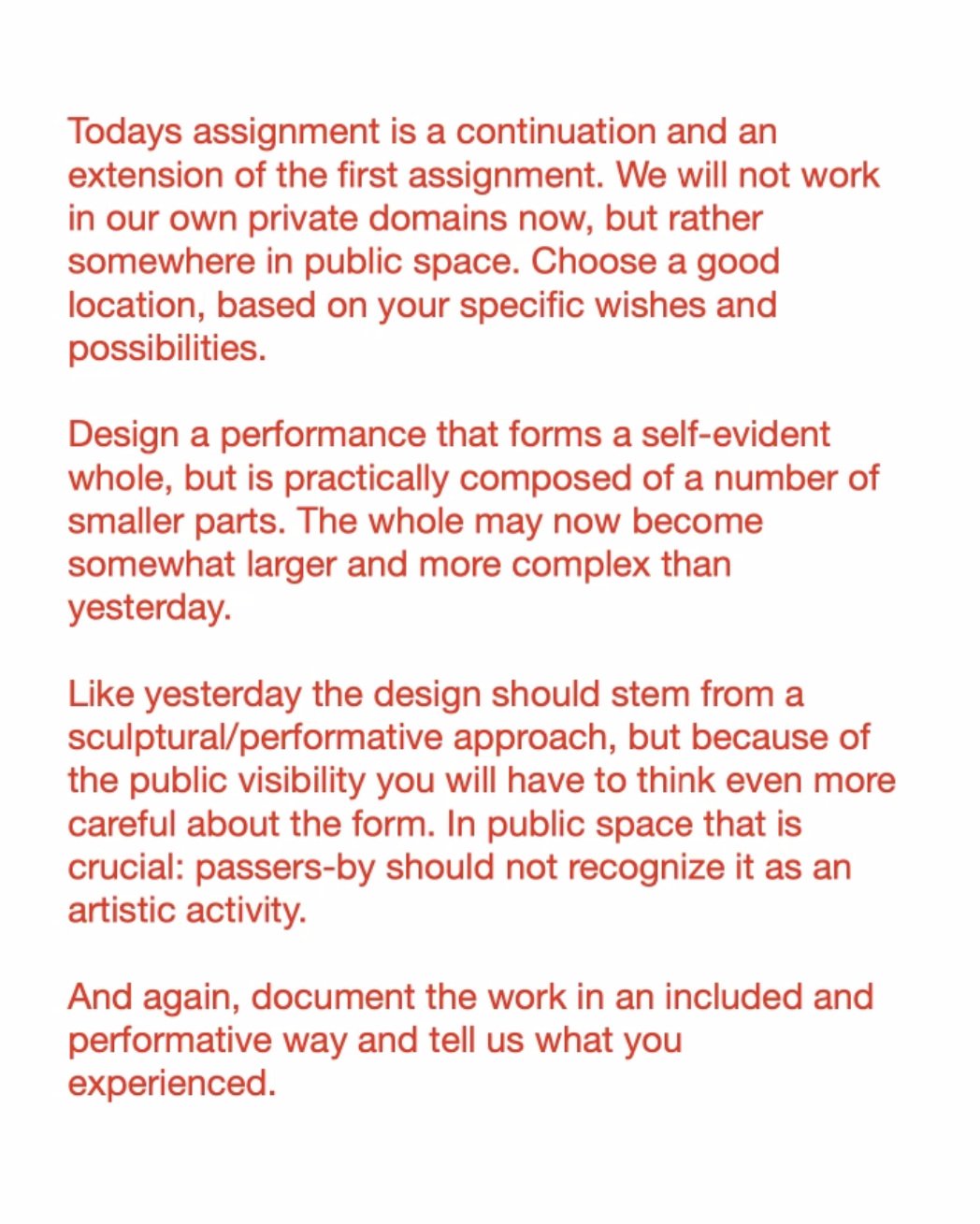

The following day, the group reconvened for the second assignment.

Once again, there were some really interesting presentations, this time a mix of video, photography, and description/story telling from Flow Festival director Carron Little, who was congratulated for being a good neighbor when observed moving trash to another spot where it was subsequently abandoned. One of the riskier performances was done by Isa Fontbona, who pulled her car over to the side of a busy road and lifted the hood, waiting to see if someone would help. No one was detected as an artist, even though John G. Boehme did some decidedly strange looking actions with a massage ball in public. Mid-performance he was greeted by two acquaintances, who did not realize he was performing.

The previous day, van Lent had mentioned that he was sorry that he had not done his own assignment. At the end of the second day of presentations, van Lent presented his piece. Beginning with the castle in a town that he knew well, van Lent selected a small object, and walked in a loop around the city center. Each time he came to a natural juncture, the first object was put down and a second object was picked up. Finally, the first object laid down was retrieved, and deposited back at the castle. What was particularly interesting was the way in which the performance was documented. Using what looked like a google map, van Lent numbered each spot where he had left an object and picked up a new one. After the performance was completed, he added a narrative about what he had picked up. The documentation was such that the viewer was invited to become a participant through the gift of a map and instructions, which they could follow as well. The workshop thus raised issues around documentation, community, and coming together as a group with shared goals. By taking performance back to its unmarked territory, van Lent restores the initial community that characterized early performance art, when it really was the case that you had to be there to know what was going on.